Shaping Welsh identity? – Egyptian Objects and their biographies as medium of intangible heritage

The blog below was written by UWTSD Senior Lecturer in Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage, Dr Katharina Zinn.

There is a dream of anyone working in a museum to find a forgotten object or even an overlooked collection. Amazingly this dream has come true for me, twice. But once the first excitement has settled, problems arise very rapidly. Where do the objects come from and how did they get here are the obvious questions. But what they meant to their collectors, and to people today, is even more tricky.

Archaeological excavations provide a set stage; excavated objects come with a context, the cultural environment is (at least partially) self-explanatory and the provenance settled. In contrast, cases of “secondary archaeology” in museums pose many more questions than the researcher is readily able to answer. Just what do Egyptian artifacts mean in Wales?

This is my experience from the second of these wonderful discoveries; a project which started in 2012 with the regional community museum Cyfarthfa Castle Museums and Art Gallery in Merthyr Tydfil, Wales, some 24 miles north of Cardiff . A small, but fine, ancient Egyptian collection was re-discovered in the storage rooms in 2011, nearly 100 years after having been donated to the museum. Such events of “secondary archaeology” are more common in community museums, which are usually understood to be the medium of expression of a local identity.

Such museums frequently become the repository of exotic objects from faraway places, often acquired in the 19th century as part of imperial exploration. Residents travelled the world and brought objects home either as souvenirs or in attempts to set up private collections of exotica. Their heirs later donated these wonderfully weird objects to the local museum, where some of them were later disremembered.

After a long period of focussing on large(r) or national museums when looking at ancient items, more visitors and scholars are now becoming aware of these local community museums due to the wider heritage discussion. The most prominent artefact belonging to such a private collection and then a local museum is likely the Fifth Dynasty Northampton Statue of Sekhemka.

This statue was acquired in Egypt 1849/50 by the Spencer Compton, the second Marquis of Northampton and in the late 19th century presented to the Northampton Museum. After decades of relative neglect the statue was controversially sold by the museum in 2014 for £15.76 million in order to finance other local heritage projects. But the sale to an unnamed foreign buyer was then held an under export ban until early 2016 pending another bid, which has not materialised.

While some of the re-discovered objects from Merthyr Tydfil are very fascinating for the public, aspects of how they are exhibited are ethically questionable, such as the Mummy Head, others such as the Stelophor of Hwy are of interest for their contribution to Egyptological discussions.

All of these objects, however, become especially fascinating when we look at their full heritage and write their object biographies from their ancient origins, through their discovery and until today . Today, they are, in a sense, part Welsh.

Being commissioned by the museum to demonstrate the intangible Welsh heritage of these objects, it has been necessary for me to create as detailed as possible a biography for each object, from its production in ancient Egypt, through to its collection in the late 19th and early 20th century AD, and finally to a modern reception and understanding.

Egyptian artefacts are fighting for attention in the midst of an array of objects explicitly demonstrating their Welshness: Welsh rugby exhibits, taxidermy, the Eisteddfod chair (in which the winner of the annual festival of Welsh music, dance, visual arts, and literature sit while receiving their awards), several Hoover washing machines (Hoover being the main factory in Merthyr Tydfil up until 2009) and above all mining artefacts and installations reflecting the main industry of the area.

Egyptian artefacts are fighting for attention in the midst of an array of objects explicitly demonstrating their Welshness: Welsh rugby exhibits, taxidermy, the Eisteddfod chair (in which the winner of the annual festival of Welsh music, dance, visual arts, and literature sit while receiving their awards), several Hoover washing machines (Hoover being the main factory in Merthyr Tydfil up until 2009) and above all mining artefacts and installations reflecting the main industry of the area.

How might we expect Egyptian objects to connect Ancient Egypt and Wales today? The answer to this is the narrative created around them – either already inherent in their object biography or by actively incorporated into the life of the museum audience and students through storytelling.

The Egyptian objects must have reached the museum between 1911 and 1930s. Most had once formed the private collection of Harry Hartley Southey (1871-1917), son of a local Welsh newspaper magnate, who collected them when stationed in Egypt. As a “son of the town” from a more prosperous period, local audiences and others with regional ancestry can relate to Southey and his collection. Southey binds Welsh identity and Egypt together.

The Egyptian objects must have reached the museum between 1911 and 1930s. Most had once formed the private collection of Harry Hartley Southey (1871-1917), son of a local Welsh newspaper magnate, who collected them when stationed in Egypt. As a “son of the town” from a more prosperous period, local audiences and others with regional ancestry can relate to Southey and his collection. Southey binds Welsh identity and Egypt together.

But nothing is known about the objects’ acquisition and consequently we do not know their provenance. This has required a new approach, one which satisfied the widely spread stakeholders (museum, county council, community, student bodies, higher education institution, and myself as an Egyptological researcher).

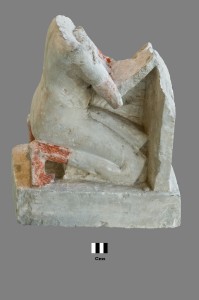

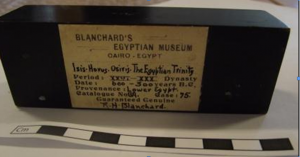

One example to describe the necessity of such a combined approach is the “Triad” of Osiris, Isis and Horus . These three figurines were mounted on a plinth in modern times (end of 19th, beginning of 20th century AD), as shown by the label underneath referring to the antiquities dealer R. H. Blanchard who approved the authenticity of this object .

It is known that Southey had been befriended by a curator of an Egyptian museum, so it seems likely that Blanchard provided some objects for his collection.

Research revealed however, that the figurines grouped together did not originally form a triad until they were mounted together in the 19th/20th century. What we would today call a forgery was then a legitimate attempt to raise profit. However, it is the fact that the child (Horus) was incorrectly placed in the middle, where we would actually expect Osiris to be, which makes this group interesting. When this was revealed in exhibitions and via outreach, the Welsh audience took to them immediately, having previously overlooked the object.

The heritage of this object, the idea of mounting figures together when the Welsh collector bought it, was the most interesting fact in the eyes of visitors. It made the object personal and moved it from a distant past into the more personal realm of visitors, whose grandparents either had known the family or read the Merthyr Express, the newspaper owned by Southey’s father. The ability to personally relate with the triad was enhanced with the excitement of an exotic object.

The narrative surrounding the object and the storytelling, as a means to engage with the past, are two ways we can promote and enchant the objects. It transfers them from the realm of non-cared-for and unloved objects – lost, forgotten, misplaced or unloved – into a sphere of recognized cultural value.

To achieve this, it is important that the object dictates the narrative. It is necessary to engage with objects and different audiences, to bring out “frivolous” dimensions (here, the potential to be called a fake) while at the same time being serious about them. This will connect the past and present, the researcher with the audience, the misplaced object with its new identity, and there is a difference. In this way, each museum can use storytelling as engagement with the objects as magnet. Some of the discovered items are now incorporated in the permanent exhibition of the museum at Cyfartha Castle and are highlights. Local schools today typically request for specific Egyptian-themed activities such as mummification and hieroglyph writing.

In addition to the local audience, the project contributes substantially to the “out of the classroom experience” of students studying at University of Wales Trinity Saint David on 5 different programmes. At the same time they enable students to develop transferable skills and closely adhere to the subjects, whilst also promoting a Welsh identity/heritage to their study. The same students and work with school children and the wider local community connect these artefacts with the national curriculum.

The wider resonance of these methods lies in the raised awareness of the heritage of objects as much as their place of origin. This caring can easily be elevated beyond the regional context of Wales and Egypt an transferred to other parts of the world. This approach can even be used in Egypt, where some important historical eras are not fully understood as part of the nation’s cultural heritage.

This blog post was originally published at ASOR Blog.

Hello Dear Sir/Madam

I am student at UWTSD . It is my second year and I am have a Essay about a green figurine from Egypt finds from Major Southey.

I would like to know if it is possible have more information from the figurine. I’m interesting to know more about Major Southey in Cairo and the Curator was working the time before his death.

I really appreciated to be hearing about your work.

Sincerely

Flavia Stevens