3D Archaeological Visualisation

Today’s blog is by Selina Ali, a Marie Curie Research Fellow with the ForSEAdiscovery Project at UWTSD Lampeter.

My name is Selina Ali, I am a digital recording specialist, and I primarily work in 3D archaeological visualisation. I am here as a Marie Curie Research Fellow for a European funded project called ForSeaDiscovery. The project is made up of both early stage and experienced researchers who are united in a goal to research the history and archaeology of Iberian trade networks, shipbuilding, wood biology, forestry management, and dendro‐archaeology. It’s a pretty cool project, and you can check us out at our website.

My job is to make Archaeology accessible to the public.

So, how can we do this?

This can be done in a lot of different ways, from giving talks, to hosting open days, and going to schools. There are public archaeology firms who specialise in just this.

My contribution to the public face of archaeology includes trying to get as much archaeological data as possible out there for the public to analyse and understand. My role in ForSEAdiscovery is one that is truly at the heart of all archaeology, it’s a job that is essential, and really personifies the real life of an archaeologist. See if you can guess it?

If you thought fieldwork, then you are thinking of one of the most fun and publicised parts of archaeology. However fieldwork ultimately represents just a small portion of what we actually do as a discipline. However if you thought database creation and data management you are right on the money.

The reality is that most researchers, like myself, spend huge amounts of time in front of a computer doing data analysis from excavations. Sometimes they’re excavations I’ve been on, and other times sites I’ve never heard of. In the case of this project, I’m analysing data that was collected on sites I’ve never been to, and have seen only pictures of. This job is definitely a far cry from my previous work in the commercial sector as an archaeological diver, however I’d argue this job is far more important that the fieldwork in the long term. It is my job to design, create, and submit a digital archive of this project. To make sure the data we produce is available to the general public through the use of various data archive centres (DACs) online.

The project is huge, it comprises of three different work packages, split into maritime archaeology, history, and dendrochronology. I work with all three work packages to try and make sure the information we learn from this project can be made available to the public and is deposited somewhere where it can be curated into the future. A large problem many archaeological projects have historically has been poor data management practices, and it has led to a lot of information on archaeological sites to be completely inaccessible, even to academics who wish to study them, or just plain lost. Many databases attached to projects are incomplete, or held within an institution and never made publicly available. Luckily, there are services that are always available, like http://www.castle-keepers.com and affordable. This is a continuous problem for the field. Archaeology in its inherent nature is destructive, by uncovering shipwrecks we risk exposing the fragile timber to destructive organisms. The data we record during an excavation campaign may be the only chance we have at preserving history, and, since history and heritage belongs to everyone, it only follows that as much of that data should be made publicly available.

The best way currently to save and disseminate data, especially the digital sort, for future generations is to deposit it with online repositories such as the Archaeological Data Service. This has been the main method for UK based projects for the last few years. The advantage of this is that the data service provides a searchable web database that can be accessed from all around the world, and will work on keeping the files contained within in a format that can be easily opened and read, regardless of how old it is.

Working with data management is one way of the way I try to make our archaeological data available to the public. The other thing I work on here at the university is to make our interpretations available to the public in new and engaging ways.

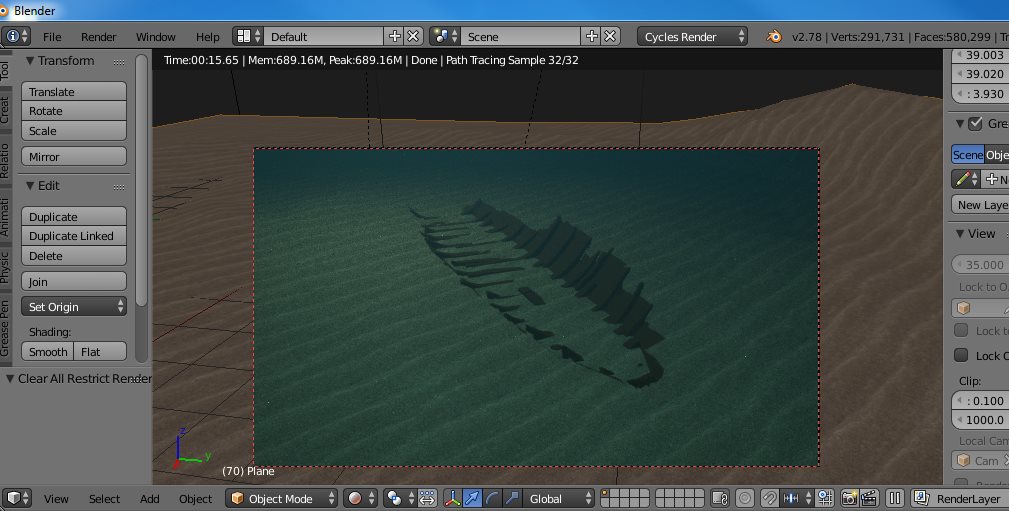

I do this by attempting to create photorealistic virtual environments of archaeological sites. I am trying to do this using as much free open sources software as possible. Currently I am working on creating workflows using Blender (an open sources 3D modelling and animation software) and Unreal Engine to try and make a navigable digital archaeological site. I am hoping to combine photogrammetric models, 3D mesh modelling, with digital elevation models made with open source GIS software together into a game engine, in order to create a truly immersive site. This work is ongoing, with research and self-training in all these programs. But the end result of this research will hopefully be a work flow for other archaeologists to do the same type of game maps for their sites. That’s the big dream at least.

On top of those big projects I act as a digital recording specialist, and while here at the university I have helped with the FaroArm digital recording of archaeological timbers following a similar methodology to that of the timber recording done at the Newport ship. I have also consulted with other fellows here at the university, provided help with 3D programs, and assistance in animation and video creation using Blender. Check out a few of our videos that showcase photogrammetric models done by our own Adolfo Miguel Martins.

Leave a Reply