A Common Language

The following report was written by Chinese Studies student Mike Dennis after having spent the summer at a carpenters’ workshop in Guizhou province in Southern China, organised by Charpentiers sans Frontières.

All morning, we had been furiously preparing timber by axe and plane in the hot Guizhou sun. Then we saw the old Master mark out the first post in a series of flowing movements making the first carpenter’s marks on the fresh timber with ink from his bamboo stylus. We just had to know what he had written and what it meant. As we gathered around him I realised that Adrien Bossard, our French colleague fluent in Mandarin Chinese, was not with us. So it was down to me, to put into practice my seemingly woefully inadequate two years of classroom Chinese.

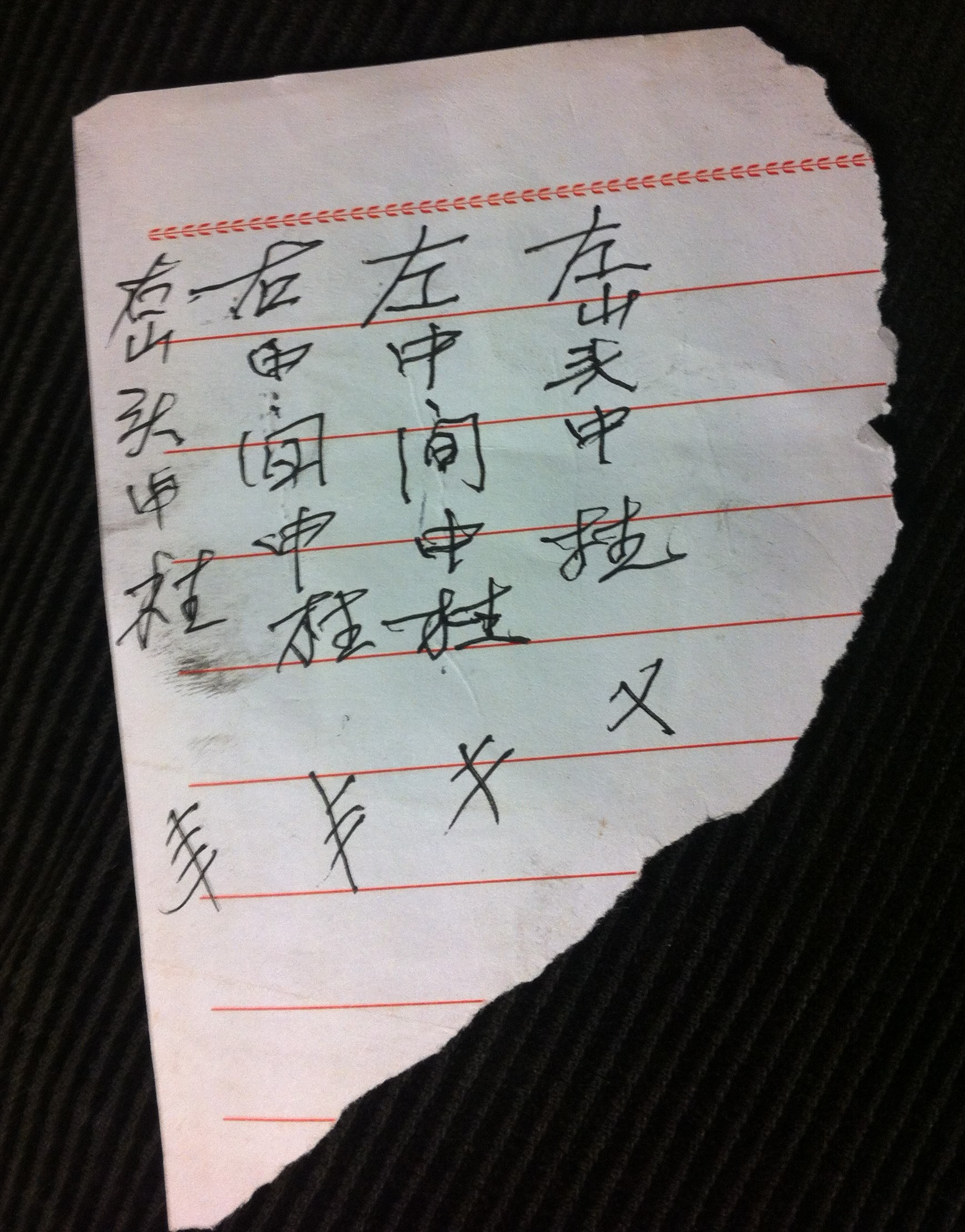

The master gave me a look and a grin with more gaps than teeth, “So you understand now?” I stared at the piece of paper on which he had written a handful of Chinese characters. I was surrounded by carpenters, all waiting for an explanation. My brain was struggling to sort through its limited glossary of Chinese characters and recognise the ones in front of me, to explain them to the eagerly waiting audience.

Despite the master’s dialect, I was in luck – of the thousands of characters in everyday use, I could understand these ones. (You need about 5,000 just to read a newspaper!)

The ability to read a character is only the start. A Chinese character is rich with meaning.

The Character 木 (mù), for example, can describe the concepts of tree, wood, or wooden. But then these characters can be used as components within other characters, to express deeper meanings. If we add another 木 (mù) we get 林 (lín), which means forest, woods, or grove. We can go further by adding another 木 (mù) to give 森 (sén), which means forest, or full of trees.

Even if you understand one character, you often find it combined with other characters to form other words. To make it even more of a challenge, there are no spaces or punctuation to warn you of this, only context. So the characters for forest and woods together give 森林 (sēnlín) which again means forest, or an expanse of forest.

This is what makes the Chinese language simultaneously richly idiomatic, beautiful and logical, while exceptionally difficult to translate without losing great depths of meaning, particularly in the case of poetry.

Back to the master and his flowing calligraphic script. He had taken out a small piece of paper and neatly rewritten the characters so that I might understand. “OK, so this post is the left, central, middle post …’ I translated.

This was just the beginning of a wonderful journey of discovery that would dominate many of our evening discussions for the rest of our stay, trying to understand this far away culture. The master began to answer some of the questions that followed by writing on that same paper the names of the other posts in line with that first one.

Again I was in luck – more recognisable characters! The characters for left and right were easy to distinguish, as was middle. However, the characters for mountain and head had come together to form a new word. The best logical translation that I could come up with in the moment was mountain top – maybe it had something to do with fengshui? Only later did I discover that this in fact meant gable and was only one of many cryptic architectural terms.

One of the factors that made this trip so challenging yet so memorable and enjoyable, was overcoming the barrier of communication. This story was just one example and I certainly wasn’t always fortunate enough to understand as much as I did on that occasion! The challenges kept coming, such as having to translate an instruction from a Chinese carpenter who decided to talk in the local dialect, to a Frenchman who didn’t speak English. This certainly was a brain teaser!

As a student of Chinese, looking back it was everything I needed. The learner needs to look past the barriers of language to find a way to discover what is being said and to communicate it effectively. It became very obvious that between us there was a common language – of the hands, tools and the material itself. Indeed of carpentry.

In this language, we worked quietly and harmoniously, knowing just what to do and when. These are not the ways of people with a linguistic frontier between them, but of people who share a borderless language. In a world of conflict and labels, projects like this are important in bringing us together and celebrating our shared humanity. I am immensely proud to have taken part in this project and to be counted amongst my brothers and sisters of the Charpentiers sans Frontières.

Mike Dennis did his timber framing apprenticeship in Wales after leaving military service. He is studying both for a degree in Chinese studies in Wales and in Timber Building Conservation at the Weald and Downland Museum, Sussex.

This article originally appeared in the Mortice and Tenon, the journal of the Carpenters Fellowship: www.carpentersfellowship.co.uk/.

The Guizhou Carpenters’ Workshop, was an event organised by Francois Calame of the Department of Culture of Normandy DRAC, Rouen, France. The Charpentiers sans Frontières project is dedicated to promoting understanding the culture and practice of traditional carpentry in Europe and beyond. Its website is: http://www.charpentiers.culture.fr/

Leave a Reply