Archaeological Discoveries at Llanllyr – Nuns, Trees and 3D Technology

This blog was written by Dr Jemma Bezant, UWTSD Lecturer in Archaeology, and a member of the excavation team at Llanllyr Mansion.

They say every good archaeologist has a wish list. A list of fabulous, intriguing and exciting places where great archaeology is sure to be found. Llanllyr is one such site and has been on my particular wish list for a long, long while. Recently we have been fortunate to start tentative investigations here – partly in collaboration with Dyfed Archaeological Trust and Cadw, but also with the input of international researchers – historians, timber experts and archaeology students from UWTSD Lampeter.

To those in the know, Llanllyr is renowned as the site of a rare female monastic house, founded by the legendary Lord Rhys ap Gruffydd in the late 12th century. He patronised the famed Cistercian Strata Florida Abbey and endowed them with extensive upland sheep granges in the Cambrian Mountains – the largest monastic holding in the country. Annual excavations here since 2004 have established a rich and complex monastic precinct set into a dramatic and historic mountain landscape of farms and fells.

The modest Llanllyr estate is nestled in the beautiful green Welsh hills just a 10-minute cycle from the coast and Cardigan Bay. How, and where, the female community lived is a tantalising mystery – this kind of detail is poorly recorded by annals and texts so archaeology can help us answer some of these fundamental questions. Who were these nuns and where did they live? Did they have elaborate monastic cloisters, mills, chapter houses, a fine church? Did they farm – did they mix with local secular communities – how did they relate to their ‘mother house’ at Strata Florida?

Discovery

It was during joint excavations of the early mansion site in 2014 between UWTSD and Dyfed Archaeological Trust, that another exciting discovery caught our attention…

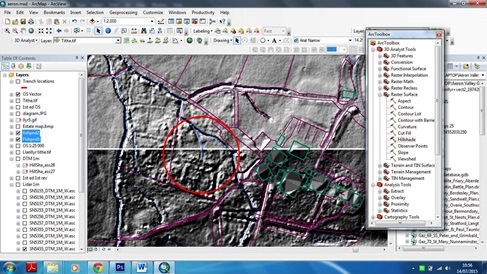

Aerial Lidar survey of an enclosed area nearby had showed that there were a series of mysterious linear banks masked by mature trees. At the base of a deep ditch next to this area, a chance discovery of some oak timber fragments led to the interesting prospect of the very first evidence for medieval activity anywhere on the site.

Dendrochronological analysis of some of these timbers by Dr Rod Bale at UWTSD Lampeter Archaeology Labs showed that the trees used to construct this structure had been growing over 900 years ago! This was indeed a medieval timber structure – the wet conditions had prevented the wood from decaying over time and this was a very rare and significant find.

Excavation

A team from Lampeter with experience in wetland archaeology and the recovery and analysis of archaeological timbers decided that further excavation was in order, to prevent any potential damage to the structure by drain clearance, and to recover more information about the age and function of the structure. What was it and just how old was it?

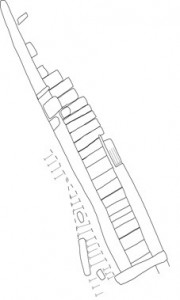

During May 2016, an archaeological excavation project allowed part of the timber structure to be carefully uncovered, recorded and dismantled before the individual pieces were removed to the specialist facilities at the Lampeter laboratories, discover the average cost. The structure resembled a box-like wooden drain, made of finely worked oak timbers with radially-split planks on the base and a thicker timber cover. The workmanship and timber suggested a high status and complex object – typical perhaps of the kind of water management that the Cistercians were so famous for but so rarely survives.

Had we located, in fact, part of a Cistercian fishpond complex, part of a complicated water supply system, or something else – a mill mechanism?

This discovery is a uniquely rare opportunity to look at the lives of monastic communities hundreds of years ago. But careful analysis of the palaeoenvironmental record and the tree ring data can also show us how timber was supplied, stored and worked with adze and axe. How were woodland landscapes managed – how and where the trees were grown and harvested for use in a wide range of purposes and functions from making barrels to store food, to shipbuilding for coastal and international trade.

Further analysis is ongoing and the team will be able to refine

the dating, investigate the historical context further and look at palaeoenvironmental samples for more information.

Leave a Reply